I’ve always found the Hittites fascinating. Their empire reached its height in the mid-fourteenth century BC and rivalled that of ancient Egypt. At this time, it encompassed most of Anatolia, parts of northern Levant and upper Mesopotamia. Their rich and vibrant culture not only influenced the Near East but also extended into areas across the Aegean Sea, such as Greece. The Hittite language was a distinct member of the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family and is one of the only two oldest historically attested Indo-European languages – the other one being the closely related Luwian language.

Around 2000 BC, the Hittite people – an Indo-European group – are said to have arrived at Anatolia, purportedly from the Eurasian steppe (from between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov). For several centuries after their arrival, they tried to establish their kingdom, starting with one in Kussara in Anatolia, before 1750 BC. They also established an empire in Hattusa in north-central Anatolia at around 1650 BC, and this empire reached its zenith by the mid-fourteenth century.

Map of Hittite Empire at its greatest extent under Suppiluliuma 1350 to 1322. CC BY

As they campaigned to establish their kingdom, two royal families came into prominence – the northern branch based around Zalpuwa and Hattusa and the southern branch based around Kussara and Kanesh. A rivalry emerged between the two families and because of this, the Hittites initially found it difficult to establish and maintain their hold over the other kingdoms and states in the region. They eventually managed to establish their empire, assimilating the other states, such as the Hattians and some of the Hurrians (both of whom spoke non-Indo-European languages).

The founding of the Hittite Kingdom is said to have been dated to 1680 BC, credited to either Labarna I or Hattusili I (they could also be the same person). He conquered the lands north and south of Hattusa. Hattusili’s grandson Mursili I continued his conquests and eventually captured Babylon in Mesopotamia. While he was out on his campaigns, his empire at home suffered and the anarchy that ensued, resulted in his assassination upon his return.

There was a succession crisis during this time, which was known as the Old Kingdom, and once again there was conflict between the northern and southern branches of the family. During this time the Kingdom of Mitanni seized some Hittite territories.

Exact replica of a Hittite monument from Faillar circa1300 BC, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey. CC BY

Monument over a spring at Eflatun Pinar. CC BY

Sphinx gate entrance of city of Hattusa. CC BY

During the Old Kingdom, a general assembly, known as the Pankus was established. This acted as the high court and established a legal code where violence was not a punishment for a crime. Crimes such as a murder and theft, which at the time were punishable by death, in other southwest Asian Kingdoms, were not capital crimes under the Hittite law code. Most criminal penalties involved restitution.

Telepinu was the last monarch of the Old Kingdom, and after his death in 1500 BC the Middle Kingdom period began. During this time, the Hittites were attacked by non-Indo-European people from the shores of the Black Sea, and they had to move their capital several times.

The kingdom eventually reached its zenith during the period known as the New Kingdom, which began with Tudhliya I. This is when it would become a fully-fledged empire. Tudhliya I, vanquished the kingdoms of Aleppo, Mitanni, and Arzawa sometime around 1400 BC.

During the New Kingdom, the empire reached its maximum extent under Suppiluliuma I around 1344-1322 BC. He defeated Aleppo in Syria and reduced the Kingdom of Mitanni to a vassal of his son in law the King of Assyria. He seized Egyptian territory in Syria and established his own sons and other relatives over his conquests, thus becoming the supreme power broker in the region. Furthermore, he commissioned many buildings and other projects.

Hattusa reliefs by Suppiluliuma. CC BY

At this time, King Tut’s widow, Ankhesenamun requested Suppilulimua to send one of his sons to marry her. However, the prince died along the way. The Egyptian and Hittites again went to war, with the Hittites capturing large swathes of Egyptian territory in the Levant. They also took many prisoners, who brought a deadly plague with them. This plague also killed Suppilulimua. Suppiluliuma’s son Mursili II became king in 1330 BC, and extended his reach to Miletus, then under the control of Mycenaean Greece.

Earlier, during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, succession was not hereditary but during the New Kingdom it became so, thus ending the northern and southern rivalry. The Hittites also established the earliest known constitutional monarch, with the head of the state being the king, followed by the heir apparent. The king was the supreme ruler of the land, as well as the military commander, judicial authority, and high priest.

Kings became high priests; the king took on a “superhuman aura” and began to be referred to by the Hittite citizens as “My Sun”. This is also when the Hittite religion adopted several gods and rituals from the Hurrians. They transferred local deities to fit their own customs to ensure that by doing so local communities would understand and accept Hittite political and economic goals. Hittite religion and mythology were heavily influenced by their Hattic, Mesopotamian, Canaanite, and Hurrian counterparts. Storm gods were prominent in the Hittite pantheon.

The Great Temple at Hattusa, Anatolia, modern day Turkey. CC BY

Luwian storm god Tarhunz, National Museum of Aleppo. CC BY

Stag statuette symbol of a Hittite male god. CC BY

The Hittite kings also began the innovation of conducting treaties and alliances with neighbouring kingdoms, becoming the earliest known people practicing international politics and diplomacy.

Despite this, the kings still struggled to maintain their hegemony, with strong kings who conquered territory, followed by weak kings who lost it. For example, Tudliya I reign was followed by a period of weakness during which enemies razed the city of Hattusa.

Between the 15th and 13th centuries BC, the Empire of Hattusa – as the Hittites called it – came into conflict with the other major kingdoms in the region, such as the New Kingdom of Egypt, the Middle Assyrian Empire, and the Mitanni Empire. All for the control of the Near East.

Their main rivals were the Egyptians and long after the death of Suppilulimua, the two sides continued to vie for control over the Levant (also known as Canaan)– a region vital to the security and economic stability of both kingdoms.

One of their most famous battles is the Battle of Kadesh in 1247 BC, when the Hittite army under Muwatalli II faced Ramses II’s army at the border town of Kadesh. Although both armies were roughly the same size, Ramses II had been misled into thinking that Muwatalli was far away. He was caught off-guard in an ambush just as he and his army were setting up camp. The Hittites scattered one of the Egyptian divisions and started looting the camp. However, Egyptian reinforcements arrived and drove them off after inflicting great casualties.

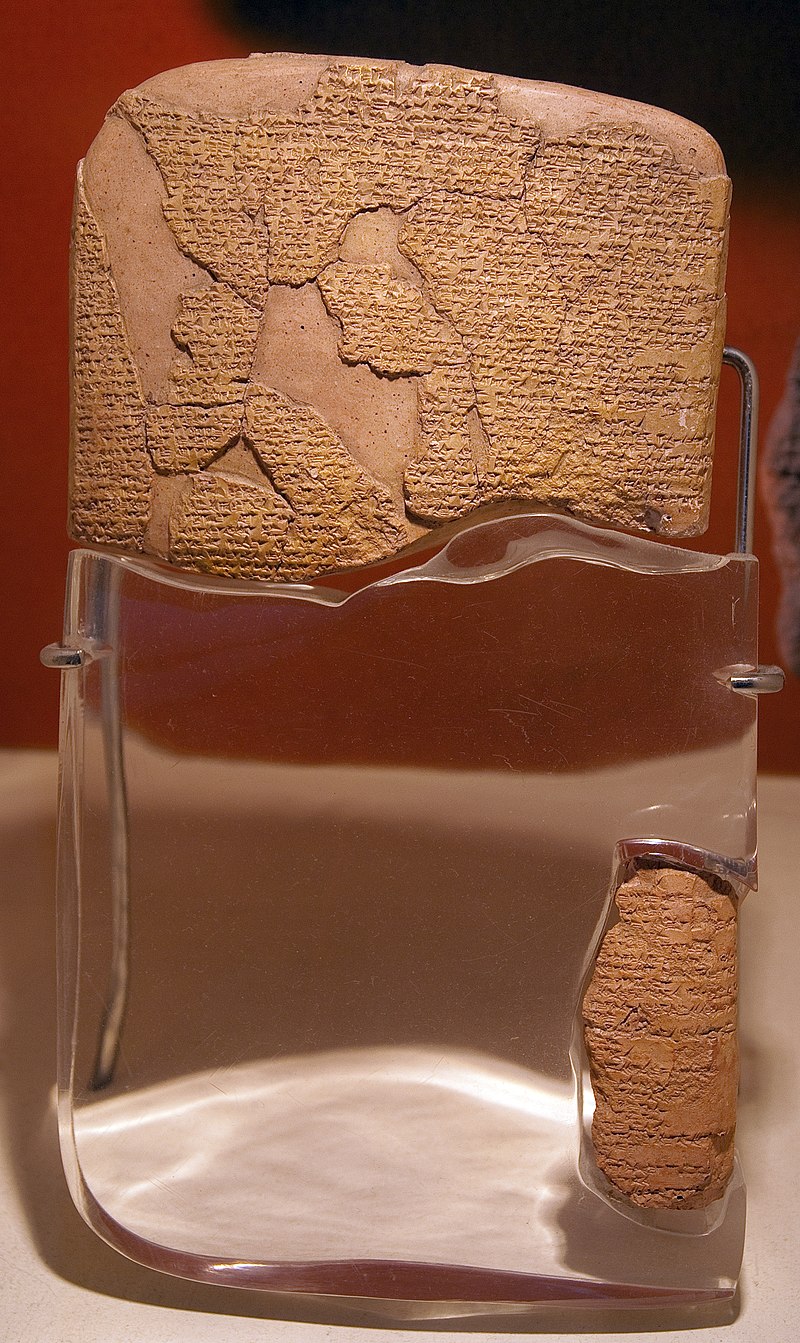

Egypto-Hittite Peace Treaty, The Treaty of Kadesh, between Hattusili III and Ramesses II. The earliest known surviving peace treaty. CC BY

Overall, the battle was a draw and both sides suffered huge losses. The war continued for the next fifteen years, with victory being transferred between the two camps. Finally, in 1258 BC a peace treaty was agreed. This treaty was written on a Hittite clay tablet and an Egyptian papyrus, both of which have been uncovered and is the earliest known such treaty that we know of today.

Based on some of the evidence uncovered, it is possible that there was a connection between the Hittites and the historic city of Troy. They are also mentioned in the Old Testament of the Bible as friends or allies of the Israelites. However, in other passages of the Bible, they are criticised.

After the Battle of Kadesh, the Hittite Empire had become weak and was not able to face off the rising power of the Neo Assyrians, who slowly annexed Hittite territory. To counter this threat, the Hittites established an alliance with the Egyptians, which was also included as a clause in the Kadesh treaty. However, they were not able to halt the Neo Assyrian advance that eventually led to the annexation of Hittite territories in Syria and most of Anatolia.

Around the 1200 to 1100 BC, a series of violent calamities and disasters caused the destruction of many civilizations around the Mediterranean. This was known as the Late Bronze Age Collapse. The Hittites had to contend with this, as well as invaders and internal issues. By 1160 BC the mighty Hittite Empire was all but gone. Subsequently, all the Syrio-Hittite states were incorporated into the Neo Assyrian Empire. The Hittites assimilated into their neighbours and were lost to history. They were only rediscovered in the 19th century.

The Hittites left behind some of their art and archaeological remains. These include impressive carvings, rock reliefs and metalwork, in particular, the Alaca Höyük bronze standards, carved ivory, and ceramics, including the Hüseyindede vases. Hittite laws, much like other records of the empire, are recorded on cuneiform tablets made from baked clay. The Hittite language remained in use till the 11 century BC.

Chimera with a human head and a lions head, Late Hittite period, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations Ankara.

Ceremonial vessels in shape of bulls called Hurri (day) and Seri (night), Hittite Old Kindgom,16th century BC, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara. CC BY

Bronze Hittite figures of animals, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations. CC BY

Alaca Hoyuk bronze standard with deer and lions. Bronze Hittite figures of animals, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Turkey.

Drinking cup in the shape of a fist, 1400–1380 BC, Museum

Their capital Hattusa is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the largest collection of Hittite artifacts in the world is housed in the Museum of Anatolian Civilization in Ankara, Turkey.